“A Comparative Study/Analysis Between the English Language and the Astori Dialect of the Shina Language based on Affixation

(Prefixation

and Suffixation)”.

ABSTRACT

The fundamental principle of this project is to examine or analyze the similarity in the process of affixation (prefixation and suffixation) between the English language and the Astori dialect of the Shina language. Mainly the native vocabulary of the Astori dialect is adopted for this research. All the borrowed and loan words are being neglected because of this we can gain awareness about the flexibility of the respective dialect. This similarity looks for the ‘formation of new words’ due to affixation, ‘modification in meaning’ because of affixation, and eventually ‘variation in the class of words’ as a result of affixation. So, all the needed data is arranged from the related texts, articles, books, websites, and native population and actual speakers of this dialect. Thus, the results of this research proved that because of prefixes and suffixes (either in the English language or in the Astori dialect of the Shina language), new words can be formed, the class of words can be changed and meaning also changes in each case. At last, this research has nominated that the flexibility of affixation of the Astori dialect is similar to that of the English language under the case study of the conversion of the ‘noun to noun’, ‘verb to the noun’, noun to the adjective’ and ‘adjective to the noun’ with the help of affixation. Hence, in the future, further studies can be conducted on the remaining parts of speech based on affixation to evaluate the similarity between both of them.

TABLE OF CONTENT

TITLE

OF RESEARCH

ABSTRACT

TABLE

OF CONTENT

CHAPTER

1

INTRODUCTION

1.1

Introduction

1.2

Research Problem

1.3

Research Objectives

1.4

Research Questions

1.5

Delimitation of Study

CHAPTER

2

LITERATURE

REVIEW

CHAPTER

3

METHODOLOGY

CHAPTER

4

DISCUSSION/FINDINGS

CHAPTER

5

CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

CHAPTER

1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Introduction

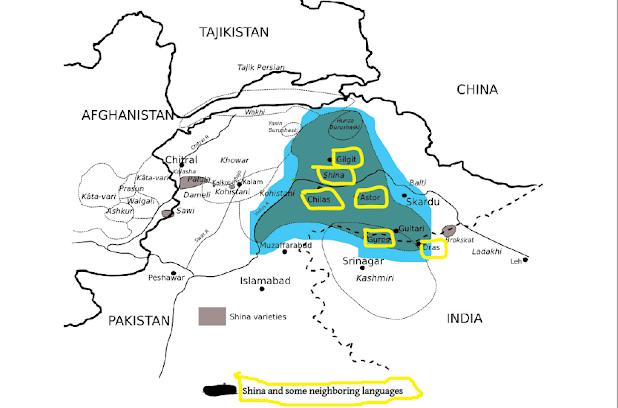

In this passage, we will look for a comparative study of the suffixation and prefixation in the English language and the Astori dialect of the Shina language. As Shina (/ʃinãã/ or /ʃiɳãã/) speaking areas are several in number in both India and Pakistan. Therefore, based on Kohistani and Schmidt (2006: 137), The Shina-speaking territories under Pakistani rule include the following: Gilgit, Tangir-Darel, lower Hunza, Chilas, Astor, and the region of Indus Kohistan, while the Shina-speaking ranges in the Neelam (Kishenganga) drainage, the Gurez and Tiliel valleys, the Drass plain, and Ladakh are controlled by India. Shina is spoken in the Gurez Valley of Kashmir Division's District Bandipora and the Drass Area of Kargil District in Ladakh Division in India's northern Jammu and Kashmir. Radloff (1992: 122-150) says that the ‘Astori dialect is most familiar (81%) with Gurezi dialect of Shina language’, which is supposed to be famous in one prominent part of Northern Areas of Pakistan. i.e. Astore and people living in this region are called /astorĩje/.

Bailey

(1924: 13-14), was the first to present an in-depth study of the grammar and

phonology of Shina. He proposed three main types (dialects) of the Shina based on

his studies: Kohistani, Astori, and Gilgiti. i.e.

a)

Kohistani (Chilasi and Kohistani)

b)

Astori (Gurezi, Astori and Drasi)

c) Gilgiti

So, Bailey believes that 'Gilgit' is the true heartland of the Shina language and that Shina-speaking places include 'Gurez', 'Tiliel’, 'Burzil Valley’, 'valleys of upper Kishenganga’, 'the districts of Astor,' ‘Chilas’, ‘Kohistan’, and 'Gilgit’, among others. Thus, “Astori, Gurezi, and Drasi make up the Astori group” (Radloff. 1992: 122).

We have a total of 31 consonants (sometimes 33, as two are repeated according to the situation) in the Gurezi (Astori) dialect of the Shina language. i.e. p, pʰ, b, t, tʰ, d, k, kʰ, g, ʈ, ʈʰ, ɖ, s, z, ʃ, ʦ, ʦʰ, h, ʧ, ʧʰ, ʒ, m, n, w, j, l, r, ɽ, ʂ, ɳ, ŋ. In addition, there are 5 primary vowels in the Gurezi Shina. Considering length and nasalization, the total number of distinctive vowel phonemes in Shina is 20. Following are the graphemes for the non-nasalized 5 short vowels and non-nasalized 5 long vowels of Gurezi Shina: /i/, /ii/, /e/, /ee/, /a/, /aa/, /u/, /uu/, /o/, /oo/. Whereas, following is given the 10 nasalized vowels: /ĩ/, /ĩĩ/, /ẽ/, /ẽẽ, /ã/, /ãã/, /ũ/, /ũũ/, /õ/, /õõ/ (Ahmed, 2020, 105-109). So, henceforth we will pin down all the necessary words of the Astori dialect according to the above distribution of phonetic transcription.

The most notable thing is that we are going to focus on just similarities between the selected languages only. Furthermore, it is worthwhile to mention that both under-examined languages have the process of affixation (prefixation and suffixation), which is very influential for new word formation, meaning changing and sometimes word class changing. Thus, our research will draw the attention of the readers toward these three topics that will cover an equal portion of both languages.

Thus,

in the English language, we can find many examples of prefixes and suffixes

that cause to creation of new words.

For instance:

Treat – retreat

Fortune –

misfortune

Fix – prefix

Thus, in the above examples ‘re’, ‘mis’, and ‘pre’ are prefixes. So, we can see there is a variation based on meaning and identity.

Similarly,

the Astori dialect has also a concept of prefixes and suffixes which are very

beneficial for new word formation.

/bό/ - /nẻbό/ means ‘don’t go’

/tʰee/ -

/kamtʰee/ means ‘to reduce’

So, in the

above-mentioned examples, ‘nẻ’ and ‘kam’ are

supposed to be prefixed. That changes the meaning and word class as

well.

In

addition, we can also highlight suffixes from the English language as well.

i.e.

Help – helpful

Change –

changeable

Sad – sadness

Thus, words including the above examples ‘ful’, ‘able’, and ‘ness’ are suffixes. Due to this, there is variation in meaning and word class also.

Moreover,

there are so many suffixes in the Astori dialect also, these are

/pijoo̗/

- /pijoo̗nããw/ means

‘drinkable’

/a̗j/ - /a̗jlό/ means ‘goat family’

/aʐó/ - /aʐónó/ means ‘inside’

Hence, the above

examples have example suffixes, that are ‘nããw’, ‘lό’, and ‘nó’. Thus,

the meaning and class of words changed, and eventually, new words formed.

Jones,

W. (1786). Furthermore, says that the comparative technique was established and

successfully used to reconstruct the parent language, Proto-Indo-European and

has been used in the study of other language families. So, without going too

deeply into the subject, let us try to lay down some basic and broad concepts

in comparative linguistics. Comparative linguistics (previously Comparative

Grammar or Comparative Philology- the humanistic study of language and

literature) is the study of the relationships or correspondences between two or

more languages, as well as the methodologies used to determine whether they

share a common ancestor. Eventually, in Europe during the nineteenth century,

comparative grammar was the most prominent branch of linguistics. The discovery

by Sir William Jones that Sanskrit was related to Latin, Greek, and German

sparked the study, also known as comparative philology.

1.2

Research Problem

This

effort will explore the prefixation and suffixation process in the English

language and the Astori dialect of the Shina language. Moreover, this study

would be influential for the investigation of similarities in the affixation

processes of both languages. Eventually, it will propose the meaning-changing

phenomena with the help of suffixation and prefixation in both selected

languages and the changing of word class as well.

1.3

Research Objectives

The

main objectives of this research are as follows:

1. To describe

the suffixation and prefixation phenomena in the English language and Astori

dialect of the Shina language.

2. To determine

the mutual resemblance of the suffixation and prefixation process among both

languages.

3. To verify the

affixation process is influential for meaning changing of the base form of the

targeted word.

4. It will also

explain whether the variation in the word class of base form occurs or

not.

1.4

Research Questions

According

to the supremacy of the topic, our study will be confined to these basic

questions so that is:

1. Do the

English language and the Astori dialect of the Shina language have an

affixation process?

2. Is there any similarity

between the suffixes and prefixes of both languages?

3. Does

affixation help to change the meaning of the base form (of the word)?

4. Does the word

class remain the same or change after (affixation) formation of a new word and

the meaning change?

1.5 Delimitation of the Study

This little effort of comparison for affixation among both languages focuses on the similarities only. So, it has no relation to the differences between the two targeted languages for their suffixation and prefixation.

Moreover, this study also highlights the prefixation and suffixation process in native words or vocabulary of the Astori dialect of the Shina language only. Thus, all the borrowed words or loan vocabulary have been omitted during this lexical study. In addition, it focuses on the class changing words, meaning changing, and new word formation.

At

last, our study is confined to some conversions including ‘noun to the noun’,

‘verb to the noun’, ‘noun to the adjective’, and ‘adjective to the noun’ only.

While the rest of the parts of speech are not included in this study.

CHAPTER

2

LITERATURE

REVIEW

Literature Review

Ahmed, M. (2020: 77) made an effort to show the purpose of ‘able’, ‘like’, and ‘-ish’, etc. The derived adjectives in the Gurezi dialect are generated by adding suffixes /-ããj/ and /-ããw/ to verbs, nouns, adverbs, and adjectives. These derivative adjectives have a lot of different meanings. For instance, when the adjectives are derived from nouns, these generally convey the meaning of ‘like’ as exemplified in:

Noun Gloss Adjective Gloss

/ʐe̗el/ forest /ʐee.lã̗ãw/,

/ʐee.lã̗ãj/ forest like

/ɡo̗oʂ/ home /ɡoo.ʐã̗ãw/ home like

/mu̗u.ʐu/ rat /muu.ʐã̗ãw/ rat like

/mu.ɳi/ tuber /mu.ɳaã̗̃w/ tuber like

Again

(Ahmed, M. 2020: 78) says that the scope of verb formation from adjectives

is very limited in Gurezi. So, we tried our best to collect some of

them. i.e.

Adjective Root Suffix Verb Gloss

/kri.du̗/ /krid/ʒ/ /-oonu/ /kri.ʒoo̗.nu/ bitter/ to become bitter

/ʐi.gu̗/ /ʐig/ /-oonu/ /ʐi.gjoo̗.nu/ dry/ to become dry

/waa̗.zu/ /was/ /-oonu/ /wa.ʒoo̗.nu/ descending/ to descend

/ʈʃii.̗mu/ /ʈʃiim/ /-oonu/ /ʈʃi.mjoo̗.nu/ thick/ to become thick

/miʂ.tu̗/ /miʂt/ /-oonu/ /miʂ.tjoo.nu/ well/ to become well

/ʈʃi.ʈu̗/ /ʈʃiʈ/ /-oonu/ /ʈʃi.ʈjoo̗.nu/ bitter/ to become bitter

/ʃu.ku̗/ /ʃuk/ /-oonu/ /ʃuk.ʒjoo̗.nu/ dry/ to become dry

Plag

(2003: 98-99) has divided prefixes among four broad categories, with an

additional miscellanea category for prefixes that could never be characterized

adequately. These would be (a) quantitative prefixes such as poly-, semi-,

hyper-, uni-, di-, bi-, multi-, etc. (e.g. polysyllabic, semi-conscious,

hyperactive, unification, ditransitive, bifurcation, multilateral); (b)

locative prefixes such as endo-, counter-, circum-, trans- retro- inter-, etc.

(e.g. endocentric, counterbalance, circumscribe, transmigrate, retroflex,

intergalactic); (c) temporal prefix like pre-, fore-, ante-, neo-, post-, mis-,

mal- etc. (e.g. preconcert, forsee, antedate, neoclassical, postmodify,

mis-trail, malfunction); (d) negative prefixes like un-, in-, de-, a-, non-,

dis-, etc. (e.g. unwrap, inactive, dethrone, asymmetrical, non-commercial,

disagree); and others like vice-, pseudo-, etc. (e.g. vice-regal,

pseudo-archaic).

According

to Quirk (1985: 1546), the affix a- (together with be- and en-) serves

primarily as a class-changing prefix along with little discrete semantic value.

Its meaning is similar to that of the progressive (like aglow = glowing).

Moreover, asleep, atop, abroad, ablaze, and apart are some other examples.

The

varieties on the boundaries of the Kashmiri-speaking zones, Gurezi as well as

Drasi, also developed possession suffix that expresses things for sexual

identity, coinciding only with the gender of a possessive noun, according to

Schmidt (2008: 21). It's most likely due to contact with Kashmiri, where the

possessive suffix inflects to agree with possessive nouns. The following are

some examples of possessive singular cases:

Gilgiti: muliay-ey nom ----- (the girl's

name)

Kohistani: Gozo-ee ʃeron ---- (the roof of the house), gozo-ee tiki ---- (home-made

bread/food)

Rajapurohit, B. (2012: 41). Singular nouns are given the plural suffix -e to render each other plural without altering their noun. Take note of the singular and plural versions that follow.

Singular forms Plural forms

[sin] `River’

[sine] `Rivers’

[pon] `Road’

[pone] `Roads

[ʧhúp] `Bank of

river’ [ʧhúpe] `Banks of river’

[ó:ʃ] `Air’ [ó:ʃe] `Different kinds of Air’

[udú:] `Dust’ [udú:e] `Dusts’

[so:r] `Ice’

[so:re] `Ices’

[kha:y]

`Pebble’ [kha:ye] `Pebbles’

[ró:ŋs] `Deer’ [ró:ŋse] `Deer’

Ahmed,

S. (2020: 4). There are following categories of

verbs that remain verbs by adding the prefixes to the

verbs as follows:

Prefix

Meaning

Verb

Verb

re- ‘again’ organize

reorganize

un- ‘the

opposite of’ cover uncover

mis- ‘the

opposite of’ apply misapply

dis- ‘not,

the opposite of’ please displease

CHAPTER

3

METHODOLOGY

Methodology

To conduct our research, we have gone through the technique of qualitative method of data collection. Therefore, we employed three primary methodologies to examine the similarities between the English language and the Astori dialect of the Shina language based on prefixation and suffixation. Thus, we reviewed articles and related documents, arranged word lists, and attempted interviews.

Moreover, after a micro-level study in affixation of both languages in articles, books and related documents, we assembled a word list of both languages based on similarity in their characteristics. Apart from them, we divided affixes with their respective words to form the combination of affixation and word.

As a result, we came up with new words, meaning a changing process and eventually word class variation as well. For instance, the conversion of nouns into nouns, verbs into nouns, nouns into adjectives and adjectives into nouns etc. Hence, this method is adopted to mark the similarity among the selected languages.

At last, several interviews have been taken with the native speakers of the Astori dialect of the Shina language and they were almost 100 in number, in which most of the participants were literate and also were familiar with the concept of prefixation and suffixation in both targeted languages. Also, the location of this sampling was the Astori speakers around the centre area of Gilgit. In addition, for the affixation in the English language we strived in different books and websites as well as in articles also.

CHAPTER

4

DISCUSSION/FINDINGS

Discussion

As previously mentioned, all the selected words for the following discussion are not borrowed from any other language, rather these are the native vocabulary of the Astori dialect of the Shina language only. So that the similarities can be extracted purely and appropriately.

Moreover,

this study primarily concentrates on the meaning-changing phenomena undergone

by affixation and also will be beneficial for observing the changing word class

and new word formation during affixation. In addition, it would also

demonstrate that sometimes only meaning changes and new words form but the word

class remains the same, while rarely affixation changes the part of speech as

well. Thus, we will try to present the previously mentioned qualities as a

similarity between both languages. Therefore, our primary target is to reveal

all these words that vary by class based on prefixation and suffixation.

Let’s discuss them one by one;

Prefixes

A prefix is an affix that is

adjoined to the left of the base of a word or comes before the base form and

plays a lexical role – which means it allows for the construction of a large

number of new words. It could be a letter or a group of letters. Prefixes

usually do not change the class of the base word but apart from new word

formation and meaning changing, this effort really focuses on the

class-changing cases also. For instance;

From Nouns to Nouns

Following are a few examples of the English

language from noun to noun conversion with the help of prefixes. So, firstly we

have nouns, then we have prefixes and last, there are nouns (which are a

combination of both prefixes and nouns). As a result, new words are formed but

the class of words remain the same. Thus, ‘tele’, ‘up’, ‘pre’, ‘tri’, ‘mis’ and

‘micro’ are prefixes. i.e.

Nouns

Prefixes

Nouns

Communication tele Telecommunication

Grade

up Upgrade

Position pre Preposition

Angle tri Triangle

Deed mis Misdeed

Scope micro Microscope

Similarly, some examples of the Astori dialect of the Shina language are from noun to noun conversion by using prefixes. So, initially, we have nouns, then there are prefixes, and eventually, we have nouns (a combination of prefixes and nouns). Consequently, new words are formed but the class of words remains the same. Therefore, all sounds like ‘/k/’, ‘/b/’, ‘/dá/’, ‘/hĩ/’, ‘/la/’ and ‘/tr/’ are prefixes of this dialect. i.e.

Nouns

Prefixes

Nouns

(Female goat) (Field)

/ãj/

/k/

/kãj/

(F.

goat)

(Cooked rice)

/ãj/

/b/ /bãj/

(Daughter)

(Grandmother)

/dĩh/

/dá/ /dádĩh/

(Barley)

(Heart)

/joo̗/

/hĩ/

/hĩjoo̗/

(Mud)

(Tail)

/mõʈĩ/

/la/

/lamõʈĩ/

(F. goat)

(Window)

/ãj/

/tr/

/trãj/

From Nouns to Adjectives

In this study, we will see how

prefixes alter the meaning as well as the word class and form new words by

converting nouns into adjectives. So, just observe the below English language

examples where we initially have nouns. There are prefixes and

eventually, there are adjectives (which are a combination of both prefixes

and nouns). So, as a result, meaning changes, new words are formed and the

class of words also differs. Moreover, ‘in’, ‘pre’, ‘post’ and ‘im’ are

prefixes. i.e.

Nouns Prefixes Adjectives

Land in Inland

War pre Pre-war

Meridian

post Postmeridian

Patient im Impatient

Similarly, the Astori dialect of the Shina language

also has the same example meaning from noun to adjective conversion by using

prefixes. So, initially, we have nouns, then there are prefixes and eventually,

there are adjectives (which are a combination of both prefixes and nouns).

Therefore, new words are formed but the class of words also changes. Thus,

‘/sĩ/’, ‘/ʃej/’, ‘/ʃe/’, ‘/p/’ and ‘/l/’ are prefixes of this dialect. i.e.

Nouns Prefixes Adjectives

(Barley) (Handsome/Beautiful)

/joo̗/ /sĩ/ /sĩjoo̗/

(sawdust)

(Unmarried

boy)

/kʰo/

/ʃej/

/ʃejkʰo/

(Cap)

(Unmarried girl)

/kʰo̗j/

/ʃe/ /ʃekʰo̗j/

(Cry)

(Old)

/roono/

/p/ /proono/

(Today)

(Shy)

/aʃ/

/l/

/laʃ/

From Verbs to Nouns

As following are some examples

of the English language in which we can use prefixes to convert verbs to nouns

easily. So, at first, we may counter verbs, then we can see prefixes and at the

end, there are nouns (which are the combination of both prefixes and verbs).

Hence, new words are formed and the class of words also changes. Thus, ‘in’,

‘over’ and ‘anti’ are prefixes of this language. i.e.

Verbs Prefixes Nouns

Come

in

Income

Lay

in

Inlay

Flow

over overflow

dote anti antidote

In the same study, we may

notice that the Astori dialect of the Shina language also has several examples

in which we can use prefixes to convert verbs to nouns. So, with the beginning we

may counter verbs, then we can see prefixes and at the end, there are nouns

(which are the combination of both prefixes and verbs). As a result, new words

are formed and the class of words also changes. Thus, ‘/bã/’, ‘/ba/’, ‘/ʐa/’, ‘/d/’ and ‘/mi/’ are prefixes. i.e.

Verbs Prefixes Nouns

(Spray) Oxen

/sãr/

/bã/

/bãsãr/

(Putting/to put)

Echo/Beating drum

/ʃõno/

/ba/

/baʃõno/

(To cry)

(Orphan)

/ró:/

/ʐa/

/ʐaró:/

(To come)

(Bull)

õõno/

/d/

/dõõno/

(To gather)

(Bone marrow)

/yó:/

/mi/

/miyoo/

From Adjectives to Nouns

In this part, we can see how prefixes

are altering the meaning as well as the word class and form new words by

converting adjectives into nouns. So, let's study the below English language

examples in which initially we have adjectives. There are prefixes and

finally, we have nouns (which are a combination of both adjectives and

suffixes). In addition, ‘sub’, ‘dis’ and ‘trans’ are prefixes of this

language. i.e.

Adjectives Prefixes Nouns

Marine

sub Submarine

Conscious

sub Subconscious

Lighted dis

Dislighted

National trans Transnational (someone operating in several countries)

Similarly, the Astori dialect of the Shina language

also has noun-to-adjective conversion by using prefixes. So, at the beginning

we have adjectives, then there are prefixes and eventually, there are nouns

(which are a combination of both prefixes and adjectives). Thus, the following

examples have ‘/ʐãʂ/’, ‘/a/’ and ‘/ʈu/’

which are supposed to be prefixes. i.e.

Adjectives Prefixes Nouns

(Curve/bend) (Head of an area)

/ʈẽrõ/

/ʐãʂ/ /ʐãʂʈẽrõ/

(White) (Eyes)

/ʃʰee̗/

/a/

/aʃʰee̗/

(Strict)

(Basket)

/ku̗ri/

/ʈu/

/ʈuku̗ri/

(Blind)

(Walnut)

/tsʰoo/

/a/

/atsʰoo/

Suffixes

A suffix is an affix that is adjoined to the right of the base of a word and changes the meaning the of base form. The most popular suffixes of the English language are –ness, -ed, -er, -est, -ity, -ly, -al, -ous, -ary, -ic, -ish, -less, -like and -y etc.

Suffixes can also be a letter or group of letters. They may change the meaning of a base word, and the class of the word and form a new word in the language. So, our primary step is to highlight these facts.

In the following examples, we

will encounter the influence of suffixes on the words of the English language

and the Astori dialect of the Shina language, which basically changes the

meaning, class and formation of new words in the language.

i.e.

From Nouns to Nouns

Here are several examples of

the English language, in which suffixes modify nouns to nouns, that have the

same class but different meanings and form new words. So, firstly we have

nouns, then we have prefixes and last, there are nouns (which are a combination

of both nouns and suffixes). Thus, ‘ess’, ‘er’, ‘yer’ and ‘ness’, are suffixes

of the English language. i.e.

Nouns Suffixes Nouns

Actor ess Actress

Paint

er Painter

Law

yer Lawyer

Poor

ness

Poorness

Tiger

ess

Tigress

Waiter ess Waitress

Similarly, there are many

examples of the Astori dialect of the Shina language from noun to noun

conversion with the help of suffixes. So, initially, we have nouns, then there

are suffixes and eventually, we have nouns (a combination of nouns and

suffixes). Therefore, ‘/ki/’, ‘/ʂek/’, ‘/ló/’, ‘/ro/’, ‘/í/’ and

‘/ŋu/’ are suffixes of this dialect. i.e.

Nouns Suffixes Nouns

(Female servant) (Bubble)

/bó:i/

/ki/

/bó:iki/

(Cow)

(House)

/go:/ /ʂek/ /go:ʂek/

(Cloud)

(Abdomen)

/áʐo/ /ló/

/áʐoló/

(Butter)

(Rock/Stone)

/gí:/ /ro/ /gí:ro/

(Mint) (Ant)

/phílí:l/ /í/ /phílí:lí/

(Fire)

(Maize

stakes)

/pʰu̗u/ /ŋu/ /pʰu̗uŋu/

From Nouns to

Adjectives

In this examination portion,

we will be familiar with the concept that how suffixes modify the meaning as

well as the word class and form new words by converting nouns into adjectives.

Also, this phenomenon can be noticed in both selected languages. So, just

observe the below English language examples in which initially we have

nouns. There are suffixes and eventually, there are adjectives (which are a

combination of both nouns and suffixes). Moreover, ‘full’, ‘able’, ‘ing’

and ‘ous’ are suffixes. i.e.

Nouns Suffixes Adjectives

Cheer full Cheerful

Fashion able Fashionable

Interest

ing Interesting

Danger ous Dangerous

Profession al Professional

Like the English language, the Astori dialect of

the Shina language also has many examples of conversion from noun to adjective

by using suffixes. So, firstly we have nouns, then there are suffixes and last,

there are adjectives (which are a combination of both nouns and suffixes).

Thus, ‘/bo/’, ‘/ʂu/’, ‘/ʈo/’ and ‘’ are suffixes. i.e.

Nouns Suffixes Adjectives

(One) (Alone/Single)

/ek/

/bo/

/ekbo/

(Fire) (Empty)

/pʰu̗u/

/ʂu/ /pʰu̗uʂu/

(Harm/Damage) (Short)

/khu/ /ʈo/ /khuʈo/

From Verbs to Nouns

The following are a few

examples of the English language in which we can use suffixes to convert verbs

into nouns very easily. So, at first, we may find verbs, then we can see

suffixes and at the end, there are nouns (which are a combination of both verbs

and suffixes). Thus, ‘ment’, ‘tion’, ‘ist’ ‘er’ and ‘ar’ all are suffixes. i.e.

Verbs Suffixes Nouns

Establish ment Establishment

Investigate tion Investigation

Accompany ist Accompanist

Rob er Robber

Beg ar Beggar

Just like the English language, our Astori dialect

of the Shina language has several examples of conversion from verb to adjective

by using suffixes. So, first, we have verbs, then there are suffixes and last,

there are nouns (which are a combination of both verbs and suffixes). Thus, ‘/ji/’,

‘/méh/’, ‘/kúr/’, ‘/j/’, ‘/kuɳ/’, ‘/khá/’

and ‘/mo/’ are suffixes. i.e.

Verbs Suffixes Nouns

(Eat) (Itch)

/khá/

/ji/ /khá:ji/

(Snore)

(Date

palm)

/khór/

/méh/

/khórméh/

(Cough)

(Puppy)

/khu/

/kúr/ /khukúr/

(Give)

(Beard)

/dã/

/j/

/dãj/

(Cough)

(Pigeon pea)

/khú/

/kuɳ/

/khúkuɳ/

(Eat) (Support/Partialities)

/khá/

/khá/

/khári/

(Eat)

(Eater)

/khá/

/mo/

/khámo/

From Adjectives to Nouns

In this area, we can observe

how suffixes are changing the meaning as well as the word class and form new

words by exchanging adjectives for nouns. So, here we will study the English

language examples in which initially we have adjectives. There are

suffixes and finally, we have nouns (a combination of both adjectives

and suffixes). In addition, ‘ness’, ‘dom’, ‘ity’ and ‘y’ are suffixes.

i.e.

Adjectives Suffixes Nouns

Sick ness Sickness

Free dom Freedom

Stupid ity Stupidity

Difficult y Difficulty

Silly ness Silliness

Like others, the Astori dialect of the Shina

language also has several examples of adjective-to-noun conversion with the

help of suffixes. So, at the beginning we have adjectives, then there are

suffixes and eventually, there are nouns (which are a combination of both

adjectives and suffixes). Thus, the following examples have ‘/jar/’,

‘/alo/’ and ‘/jaa̗r/’, which can be considered

suffixes of this regional language. i.e.

Adjectives Suffixes Nouns

(Small) (Poverty)

/ʃuni/

/jar/ /ʃunijar/

(Less) (Blanket)

/kam/

/alo/ /kamalo/

(Bitter) (Bitterness)

/ʈʃi.ʈu̗/

/jaa̗r/ /ʈʃi.ʈjaa̗r/

(Well) (Wellbeing)

/miʂtu̗/

/jaa̗r/ /miʂtjaa̗r/

(Light) (lightness)

/loo̗ku/

/jaa̗r/ /lok.jaa̗r/

CHAPTER

5

CONCLUSION

Conclusion

The

flexibility of every language allows their different aspects to be compared.

That’s why we have made a comparison between the English language and the

Astori dialect of the Shina language based on prefixation and

suffixation. Thus, this little effort was about similarities found in both

languages according to the selected topic. As we have highlighted previously

the dialects of Astori have three subparts named Astori, Gurezi and Drasi. So,

we collected our primary data from pre-existing articles, books, grammar data etc. Other required data is gained from the native speakers of

these dialects living around the centre of Gilgit City. Moreover, we introduced

the concept of prefixation and suffixation, then mentioned their examples from

both languages and elaborated on all the variations that occur due to the

application of affixation. In addition, we tried our best to portray the

results coming from the suffixation and prefixation phenomenon. This proved

that the meaning of words can be changed with the help of affixation,

similarly, new words can be formed because of prefixation or suffixation and

eventually, we can modify the class of base words that undergo the affixation

process. Finally, both languages have an affixation process and the same

results can be extracted from them after adding prefixes and suffixes. Thus,

this could be the essential similarity between both languages and hence, this

is the basic goal of conducting our research. i.e. the consequences of applying

prefixation and suffixation have the same impact on both languages which is the

greatest similarity among them.

References

Bailey, T. G. 1924. “The grammar of the Shina (ṢiṆā) language”. London: The

Royal

Asiatic Society.

B. B. Rajapurohit. 2012. “Grammar of Shina Language and Vocabulary”, p. 41.

Kohistani, R. - Schmidt, R. L. (2006): Shina in Contemporary Pakistan. In: Saxena,

Anju – Borin, Lars

(eds): Trends in Linguistics: Lesser-Known Languages

of

South Asia. Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter, p. 137.

Musavir Ahmed, 2020. “A Descriptive Grammar of Gurezi Shina”. P. 77-78.

Peter C. Backstrom and Carla Radloff (eds.). 1992. “The Dialects of Shina”.

Sociolinguistic

Survey of Northern Pakistan. Volume 2. 122-150.

Plag, Ingo (2003), “Word-Formation in English”, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

Quirk, Randolph,

Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, Jan Svartvik (1985), “A

Comprehensive

Grammar of the English Language”, Pearson Education,

Harlow.

Ruth Laila Schmidt and Vijay Kumar Kaul, 2008, pa. “A Comparative Analysis of

Shina

and Kashmiri Vocabularies", p. 21.

Saza Ahmed, 2020. "A Comparative Morphological Approach to Class

Maintaining

Derivational Affixes in English and Kurdish", Vol: 6. “Journal

of

University of Human Development”, p: 4.

Sir William Jones, 1786. “Language Families, and Indo-European”.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.1992.12098279. Garland Cannon (1992).

Comments

Post a Comment